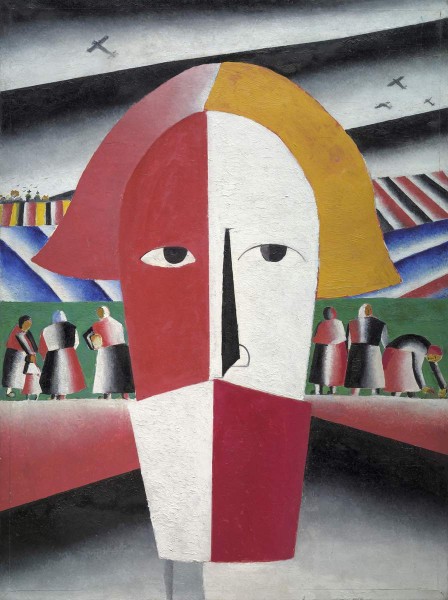

Kazimir Malevich’s Head of a Peasant can be regarded as a prophetic image. It also contains the key to the understanding of the artist’s entire Peasant Cycle. Malevich paints Head of a Peasant in the same way as an icon-painter paints an icon, with the real life sensations acting as a source enriching ageold tradition. The sullen peasant depicted on the canvas recalls the early Orthodox icon The Life of St Nicholas, a Russian form of the image of Christ Furious Eye, and the characters of traditional Russian wood engravings (lubok). The background for the peasant’s icon-like face is a scene of harvesting, which accompanies many of the works of Malevich’s Peasant Cycle. Russian Museum: From Icons to the Modern Times. Palace Editions, St Petersburg, 2015. P. 343.

Malevich himself declared that the year 1928 marked a new stage in the development of his art. He created a series of artworks in which the immateriality and lightness of Suprematism was combined with a more figurative approach that used color and form to breathe life into a new perception of the pictorial space and of man’s place within it. These artworks, produced between 1928 and 1929, belong to Malevich’s so-called «Second Peasant Cycle».

Malevich did not choose the «peasant» theme arbitrarily. In his autobiography, he wrote that he had always tried to follow the peasant example in all aspects of his life, including his clothes, his manners, and even his diet. He admired the peasants’ houses, their embroidered clothes and the way in which they decorated their belongings. For Malevich, the faces of the figures in religious icons were, in reality, the faces of peasants.

This painting, titled Head of a Peasant, combines elements from his portrait of Ivan Kliun, the peasant genre, and religious imagery in order to create a kind of «Post-Suprematist Icon». The tension and anger of this masculine face, against a background frieze of peasants and plowed fields, is reminiscent of the icon known as «Savior with the Angry Eye» in the Cathedral of the Assumption in Moscow. The planes flying through the sky, which is edged with black lines, create a striking sense of dissonance as the emerging technological era comes into contact with folk traditions.

From a young age, Malevich had viewed the urbanized world of automobiles, factories and industry as a terrible and aggressive force. For him, it stood in complete opposition to the soil and the fields where the peasants labored; where people rose with the sun and sang songs as they worked.

After moving to Moscow, and then to St Petersburg, up until his death Malevich always tried to spend his free time closer to nature: specifically, in the village of Nemchinovka, which was near Moscow. The village, which was also home to the house of his second wife, the children’s author Sofia Rafalovich, became Malevich’s most precious retreat.